A research team at the Quarta Colônia Palaeontological Research Support Centre in southern Brazil excavates a fossil site.Credit: Janaína Brand Dillmann

Rain can be a friend or foe for palaeontologists. It can wash away soil or erode rocks, potentially revealing thrilling fossils, or it can cause already-exposed, delicate specimens to crumble.

Prized dinosaur fossil will finally be returned to Brazil

Nowhere is this truer right now than in southern Brazil. In May, devastating floods in the state of Rio Grande do Sul uncovered pieces of bone from at least 35 ancient animals, including a 233-million-year-old skeleton that is among the oldest dinosaur fossils in the world. But intermittent rain showers and wet conditions since then have researchers racing to recover other smaller, more-vulnerable specimens that are also precious.

Adding to the urgency is the unprecedented nature of the floods. Between 27 April and 27 May, the state’s capital, Porto Alegre, saw about 66 centimetres of rain — almost half of what it normally gets in one year, and many other cities across the state have flooded, too. Some palaeontological sites are still under water.

“If palaeontologists are not there to collect material when it starts showing, we risk losing some of it forever,” says Leonardo Kerber, coordinator of the Quarta Colônia Palaeontological Research Support Centre (CAPPA) at the Federal University of Santa Maria in São João do Polêsine.

Exceeding expectations

Since the downpours in May, palaeontologist Rodrigo Temp Müller and his colleagues at CAPPA have intensified their monitoring of excavation sites near São João do Polêsine, which is about 280 kilometres west of Porto Alegre.

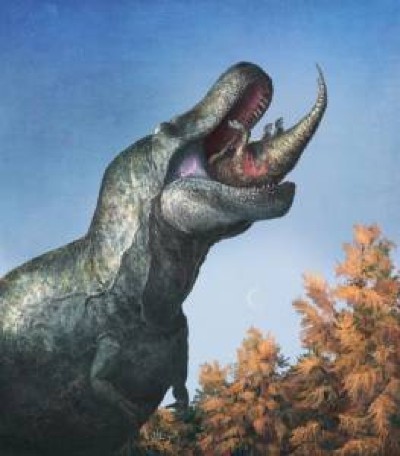

Palaeontologists uncovered these bones, belonging to a 2.5-metre-long carnivorous dinosaur called a herrerasaurid, after floods ravaged southern Brazil.Credit: Rodrigo Temp Müller

On 15 May, about two weeks after torrential rains caused the banks of Rio Grande do Sul’s river system to overflow, Müller and the team uncovered a 2.5-metre-long fossil of a carnivorous, bipedal dinosaur belonging to the Herrerasauridae family. “We were sure we’d find something after the heavy rains,” Müller says, but the specimen still exceeded expectations.

Herrerasaurids emerged and vanished during the Triassic period (about 250 million to 200 million years ago) and were the “first top predators to appear among dinosaurs”, says Aline Ghilardi, a palaeontologist at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte in Natal, Brazil. They would eventually be replaced during the Jurassic period (200 million to 145 million years ago) by larger dinosaurs called theropods, which include bipedal, three-toed meat-eaters such as Tyrannosaurus rex.

Some researchers argue that the herrerasaurids were the first theropods, but this designation is still controversial. “This is why the findings of CAPPA are so important — they can help us solve open questions like this,” Ghilardi says.

Working against the weather

But it has been difficult to celebrate the discovery, says Müller. The floods affected almost 2.4 million people in Rio Grande do Sul, including 183 individuals who died and 27 who are still missing, according to local authorities. “People near the excavation site lost their houses,” he adds.

Since their fossil find, Müller and his colleagues have taken slabs of rock and soil containing the Herrerasauridae specimen back to their laboratory to carefully extract the bones. They have removed enough material so far to be cautiously excited: they think it might be the second-most-complete fossil of its kind ever found.

Record-breaking floods submerged parts of Rio Grande do Sul’s capital, Porto Alegre, in early May.Credit: Carlos Macedo/Bloomberg/Getty

But the team can’t relax just yet. With rain continuing to fall intermittently, the researchers are still rushing to save fossils of many smaller animals — ones that don’t usually make headlines but that are still important. “Everybody likes big dinos,” Kerber says. But “the largest species diversity is always among the smaller animals”. Such fossils help palaeontologists to reconstruct how species evolved and uncover details about the environments in which they lived.

The tiniest bones of animals both big and small are also a concern. They are the first to disappear when rain hits an excavation site, says Juan Cisneros, a palaeontologist at the Federal University of Piauí in Teresina, Brazil. “They’re rare and harder to find.” Ear bones in small reptiles, for example, can be just millimetres long, yet they reveal a lot about an animal’s brain and how intelligent it might have been.

Treasure trove

About a week ago, the CAPPA researchers uncovered the skull of a baby rhynchosaur — a parrot-beaked, herbivorous reptile that could grow on average to about 1 metre long and dominated Earth during the middle to late Triassic (247 million to 200 million years ago). Although these rhynchosaur fossils are abundant, Müller says, “they’re important exactly because they are abundant”. In particular, they play a stratigraphic part in research because they mark Triassic sites, he adds. “Where there’s a rhynchosaur, there probably will be a herrerasaurid.”

Facelift for T. rex: analysis suggests teeth were covered by thin lips

Now, the team is excavating a cynodont fossil — the skeletal remains of a mammal-like reptile that lived from about 260 million to 100 million years ago and ranged from the size of a rabbit to a large dog. These reptiles are the ancient ancestors of mammals, which are the only cynodonts remaining, Kerber says.

The fossil-rich region where the palaeontologists are working hosts 29 excavation sites, 21 of which the CAPPA team has been able to access since the floods, according to Müller and Kerber. Four are still almost completely under water.

One thing working to their advantage is that CAPPA is so close by. “We don’t need to plan long excavation trips, but can be in the field every week,” Müller says. The next challenge the researchers will face is what to do with all the fossils they’re recovering — the centre does not have a museum. “It would be important to have one, not only to store the fossils we find,” Kerber says, “but also to educate the local population on how rich their region is.”