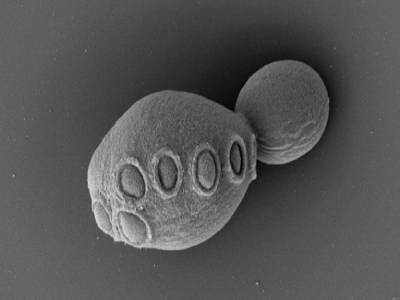

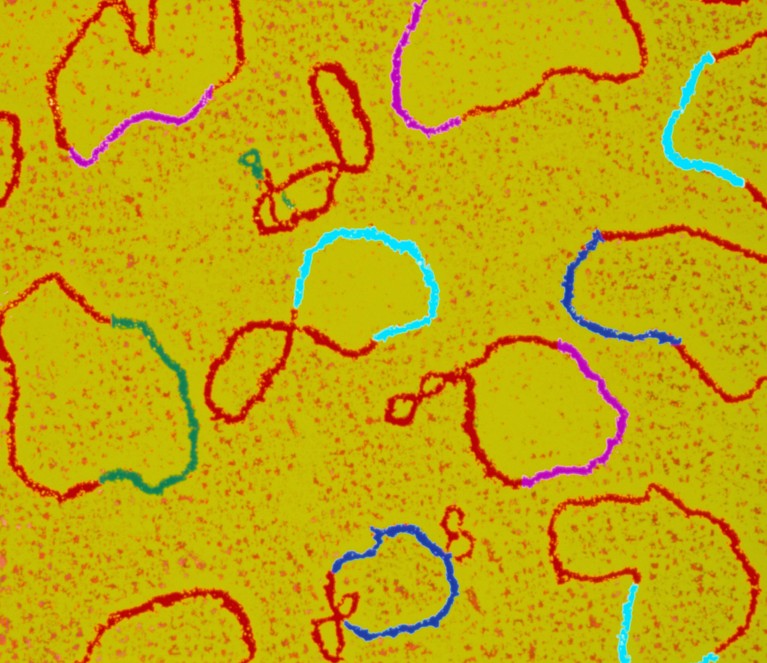

Plasmids (shown here in a coloured transmission electron micrograph with various genes highlighted) are circular DNA structures used in biology laboratories.Credit: Dr Gopal Murti/SPL

Laboratory-made plasmids, a workhorse of modern biology, have problems. Researchers performed a systematic assessment of the circular DNA structures by analysing more than 2,500 plasmids produced in labs and sent to a company that provides services such as packaging the structures inside viruses so they can be used as gene therapies. The team found that nearly half of the plasmids had design flaws, including errors in sequences crucial to expressing a therapeutic gene. The researchers posted their findings to the preprint server bioRxiv last month ahead of peer review1.

The study shines a light on “a lack of knowledge” about how to do proper quality control on plasmids in the lab, says Hiroyuki Nakai, a geneticist at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland who was not involved in the work. He was already aware of problems with lab-made plasmids, but was surprised by the frequency of errors uncovered by the study. There are probably many scientific papers that have been published for which the results are not reproducible owing to errors in plasmid design, he adds.

Wasted time

Plasmids are popular tools in biology labs because bacteria, including the widely used model organism Escherichia coli, use the structures to store and exchange genes. This means that biologists can make designer plasmids containing various genes of interest, and then coax E. coli to take them up and make lots of copies.

Reproducibility crisis: Blame it on the antibodies

Bruce Lahn, chief scientist at VectorBuilder, a company based in Chicago, Illinois, that provides gene-delivery tools, says that he and other biologists have been noticing problems with plasmid quality for years. For example, when Lahn was a professor at the University of Chicago, a graduate student in his lab spent six months trying to reproduce two plasmids that had been reported in the scientific literature. “We didn’t think twice about the quality of the plasmids, but then the experiment wouldn’t work” because the plasmids contained errors, he says.

Now at VectorBuilder, Lahn says he’s faced with the issue all the time — so he decided to evaluate it systematically. When customers submit error-laden plasmids, “it ends up wasting a lot of time”, and the extra steps involved in doing quality control add to the cost of producing the plasmids and packaging them into viruses, he says.

The VectorBuilder team’s analysis found a hodgepodge of errors in the more than 2,500 plasmids it evaluated. Some contained genes that coded for proteins toxic to E. coli, which means that they could slow or stop the growth of the organisms biologists rely on to replicate their plasmids. Others, destined for packaging into viruses, encoded proteins toxic to those viruses. And some contained repetitive DNA sequences that can accumulate mutations inside plasmids.

Checking for errors

The most rampant errors Lahn and his colleagues found were related to a key gene-therapy tool. Therapies are often packaged into adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), which are mostly harmless and can ferry treatments to cells. When making the plasmids for these AAVs, researchers sandwich a therapeutic gene between sequences called ITRs, which play a crucial part in ensuring that the gene gets packaged into the virus for delivery. In essence, these sequences send a biological signal to cells that says “I belong in this virus”. But the team found that about 40% of the AAV plasmids in the study had mutations in the ITR regions that could garble this important message. If researchers were to use these misdesigned plasmids, their gene therapy might not work — and it could take the scientists a long time to find out why.

Engineered yeast breaks new record: a genome with over 50% synthetic DNA

Mark Kay, a paediatrics and genetics specialist at the Stanford School of Medicine in California, has also seen at first hand that plasmid errors can delay lab projects. But he’s confident that scientists can spot and fix these errors. He says that gene-therapy researchers are familiar with potential ITR issues, and that errors are unlikely to lead to problems in clinical settings. That’s because regulatory agencies such as the US Food and Drug Administration have stringent standards that require researchers to carefully analyse their plasmids before using them in the clinic.

Nakai says checking plasmids for errors by sequencing them could alert researchers to the problems highlighted in the study. A few companies, including Plasmidsaurus in Eugene, Oregon, and Elim Biopharmaceuticals in Hayward, California, offer plasmid sequencing for about US$15.00 per sample, says Nakai, who has no financial interest in either company. He also recommends that new lab members spend time learning from experienced plasmid constructors; it’s a tedious, artisanal process, he says, but if you get it wrong, it can waste a tremendous amount of time and money.

Another way for labs to avert issues is by publicly sharing their plasmid sequences in open-access repositories, says Melina Fan, chief scientific officer of the non-profit organization Addgene in Watertown, Massachusetts. Addgene provides one such repository, Fan says, and it “sequences the deposited plasmids and shares the sequence data via its website for community use”. Verification of plasmids is important, she adds.

Lahn hopes that his team’s analysis will draw researchers’ attention to the fact that these workhorse lab tools are often taken for granted. “The health of the tool is not something people question,” he says, even though they should.