Anne Wyllie has long been interested in what saliva can reveal about disease.Credit: Joe Buglewicz for Springer Nature

As the COVID-19 pandemic took hold in 2020, Anne Wyllie, a microbiologist at the Yale School of Public Health in New Haven, Connecticut, joined the institute’s emergency response team. One of the questions it faced was how the team could help with testing shortages, which were both hampering understanding of how the disease was spreading and delaying people from isolating to stop disease spread.

Wyllie had long worked with saliva as a sample material, searching for evidence of Streptococcus pneumoniae in people without obvious signs of infection. She started thinking about whether the saliva could reveal the presence of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. “I don’t know how naive it was, how optimistic it was, how desperate it was, but I just wondered whether saliva could help us overcome some of the challenges,” she says.

She started experimenting with testing spit, rather than cells scraped from high up in the nose, and found that the results were remarkably accurate. By the end of March, she and her colleagues had evidence that saliva worked at least as well nasal swabs, and possibly better1. Wanting to get their new protocols out to as many testing laboratories as possible, they started sharing them widely. In 2022, they formed a company, SalivaDirect.

Nasal swabs had several drawbacks. One was a supply-chain issue: it was hard to get enough of them to serve the massive testing effort being rolled out. Another was that they were accurate only if used correctly, and not all health-care workers were experienced enough to take the samples from as far up the nose as needed. When the workers did do it correctly, nobody liked the test — some people described the feeling as like being poked in the brain. Wyllie says that public-health researchers such as herself asked health-care workers to take two tests each time, one for diagnostics and one for research. The request wasn’t well received. “Once a person has had one swab,” she says, “they don’t really want a second.”

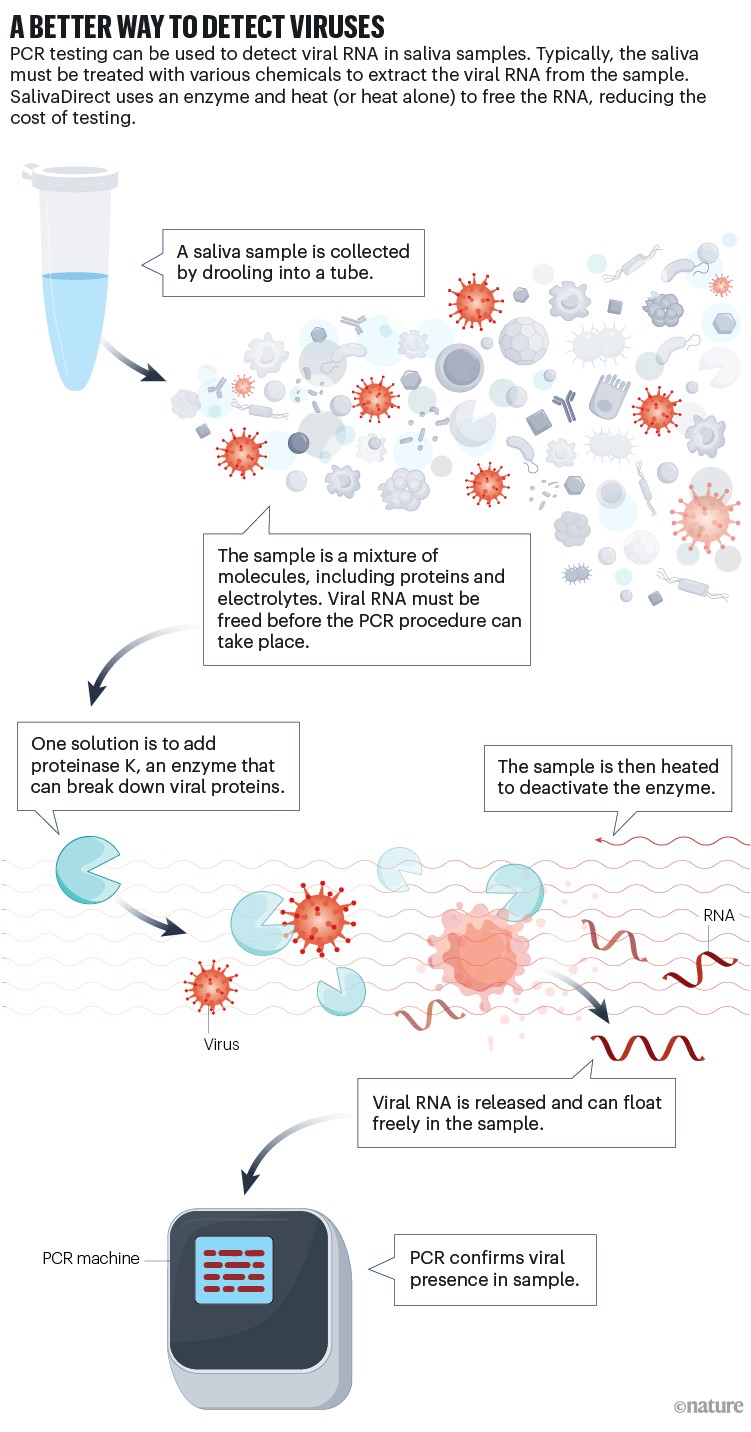

Saliva, however, is more readily accessible — people are simply asked to drool into a tube (spitting could propel infectious droplets into the air and put health-care workers at greater risk of exposure). Testing saliva might even be better at revealing virus that could be hiding in certain niches — coming up from a sore throat or down from the nose in a post-nasal drip, for example. But the tests still faced the same bottleneck that the swabs did: the time-consuming and expensive process of running the samples through a PCR system. Under existing procedures, labs had to treat the sample with an assortment of chemical buffers to extract the viral RNA from other components in the sample. That step took about 40 minutes and required the purchase of various chemicals and plastic sample plates, driving up cost and creating waste.

SalivaDirect’s solution was to find a way to skip the extraction step. Using proteinase K, an enzyme that breaks down proteins, the researchers could enable the viral RNA to move about more freely in the sample, then apply heat to deactivate the enzyme (see ‘A better way to detect viruses’). They later discovered that they did not have to use the proteinase at all, and that a pattern of heating that involved various temperatures at different times could itself release the RNA. That leaves individual labs with the option of either using or skipping the proteinase, depending on what works best with the lab’s normal set-up. Either way, scientists can then run the same quantitative PCR procedure that works with nasal swabs, which involves making enough copies of the virus’s genetic material for it to be detected. The result, Wyllie says, is a test that costs $0.50–1 per sample to run, as opposed to $9–12 per sample for tests that include chemically driven RNA extraction.

Infographic by Alisdair Macdonald

The next step was to show that SalivaDirect’s technology was as good at detecting the virus as the nasal swab was. That required the researchers to take both types of sample from the same people and compare results. In a study of health-care workers, a small number of people who tested negative with the nasal swab were shown by the saliva test to have the virus. When these people retook the nasal test, they then tested positive. “It was kind of buried in our paper because it was such a small number,” Wyllie says. Later studies, however, confirmed that SARS-CoV-2 could be detected earlier with saliva than it could be with swabs2.

Another study3 compared samples from basketball players. The US National Basketball Association (NBA) was eager to test players regularly so it would know if it was safe to play scheduled games, and even contributed a reported $500,000 to the research. In August 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an emergency use authorization for the SalivaDirect test. That authorization is still in effect, and the company is working on getting the test approved for non-emergency use.

This was not the only saliva-based test given the green-light by the FDA. An assay developed by researchers at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and RUCDR Infinite Biologics — a Rutgers spin-off firm in Piscataway, New Jersey, now known as Sampled — also won approval. That test, however, used the more expensive extraction step.

The non-profit route

To make its test accessible to more people, SalivaDirect validated it on reagents and equipment from different suppliers, so labs wouldn’t have to buy new equipment and could use whichever supplies were more available or affordable. Since August 2020, SalivaDirect has updated its emergency-use authorization more than two dozen times to allow more reagents to be used, and it continues to validate others. All labs running the test must be certified under the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Clinical Laboratories Improvement Amendments rules.

SalviaDirect’s method eliminates the need for expensive chemicals in disease testing.Credit: Joe Buglewicz for Springer Nature

In October 2022, SalivaDirect spun out of Wyllie’s lab as a standalone non-profit company, with Wyllie as board chair. The non-profit status was important for furthering the science, says executive director Yasmine Ali. “We wanted to make sure that the focus of SalivaDirect remained on promoting saliva as a sample type for diagnostics, rather than focusing solely on how much money could potentially be made,” she says.

Being a non-profit organization also meant that labs that the team had worked with, and that had shared their data with the company to help advance the science, would not see SalivaDirect as a competitor and would continue such sharing, Ali says. Members of this network, which includes producers of reagents and testing instruments as well as academics, pay a membership fee that gives them access to data and experts. The company also hosts an annual conference on equitable disease testing around the world.

SalivaDirect is considering setting up a for-profit arm, which would develop saliva-based tests while the non-profit side focuses on pushing the diagnostic value of spit. The company is already working on assays that would replace swab tests for influenza A and B, and for respiratory syncytial virus. Future tests might cover sexually transmitted infections such as gonorrhoea. During the mpox outbreak in the summer of 2022, the company tested saliva-based assays for that disease and found that they worked well.

As well as membership fees, SalivaDirect has raised funds through sponsored research projects for diagnostics companies. And in November 2023, the company won a US$3.2 million grant from the National Institutes of Health through its Rapid Acceleration of Diagnostics programme, which promotes the development of COVID-19 tests.

The low cost and relative simplicity of the saliva-based assay also makes it possible to reach more communities, Wyllie says. Early in the pandemic, SalivaDirect partnered with Flambeau RapidX in Madison, Wisconsin, to create a lab in a van to provide free testing to underserved communities. People at markets or local events could provide a saliva sample and contact information and get results in a couple of hours. The company is also working on a sample-collection kit that could be distributed through vending machines, then sent to a lab for processing. Beyond the United States, the test has been validated in 13 countries, including Ireland, Colombia and Bangladesh, Ali says, and the company is working on offering the test in Malawi. “It’s so well suited to low-resource settings,” Wyllie says.

The company’s technology is broadly applicable and based on solid science, says Christian Uhrich, a venture capitalist at M Ventures in Amsterdam, who served as one of the judges for the Spinoff Prize 2024. Other sample-collection options are “more invasive and hence less user-friendly”, he says, and SalivaDirect’s approach to diagnosing disease could prove to be significant for society.

Wyllie has long been interested in what saliva can tell scientists about disease. During her PhD at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, her supervisor was leafing through studies of S. pneumoniae from the early 1900s, and pointed out to her that back then it was saliva, not a nasal swab, that was the sample of choice for detecting the bacterium. In those days, physicians found a lot more of the bacterium in older adults than they do now, and her supervisor wondered whether that had something to do with differences in testing. So they set up a study4, looking at school-age children, who were thought not to harbour the bacteria very often. “I went to a school and just got a lot of saliva from school kids,” Wyllie says. “We found 50% of kids had it.” Since then, she’s been optimizing and validating a lot of quantitative PCR assays using saliva to detect the bacterium.

Her focus won her the sobriquet of ‘spit queen’, from the dean of Yale’s School of Medicine. “It’s a moniker that’s definitely stuck with me,” she says. “I’m fortunately not offended by it.”