By mid- to late November every year, a pall of noxious air settles over the entire Indo-Gangetic Plain, stretching from eastern Pakistan to Bangladesh. This year, the haze was visible in satellite images and disrupted daily life in large cities such as Lahore and Delhi, leading to school closures and weekend curfews reminiscent of COVID-19 lockdowns.

The causes of this phenomenon are well known. Pollution levels typically begin to surge during the autumn festival of Diwali because of the widespread use of fireworks. The situation worsens as farmers burn leftover rice-paddy stubble to prepare fields for the winter (rabi) crop, following the harvest of the summer (kharif) crop. These seasonal factors, combined with background pollution from vehicular and industrial sources, create a public-health emergency in the region every year.

On cue, on 18 November this year, Delhi’s Air Quality Index soared to 1,700 — far exceeding the safe limit of 50 set by the World Health Organization (WHO). Lahore in Pakistan had recorded a value of 1,100 a few days earlier. Because the Indo-Gangetic Plain is one of the most densely populated regions globally, the number of people affected would be in the millions — making the north Indian pollution plume one of the world’s biggest public-health challenges. Yet it is solvable.

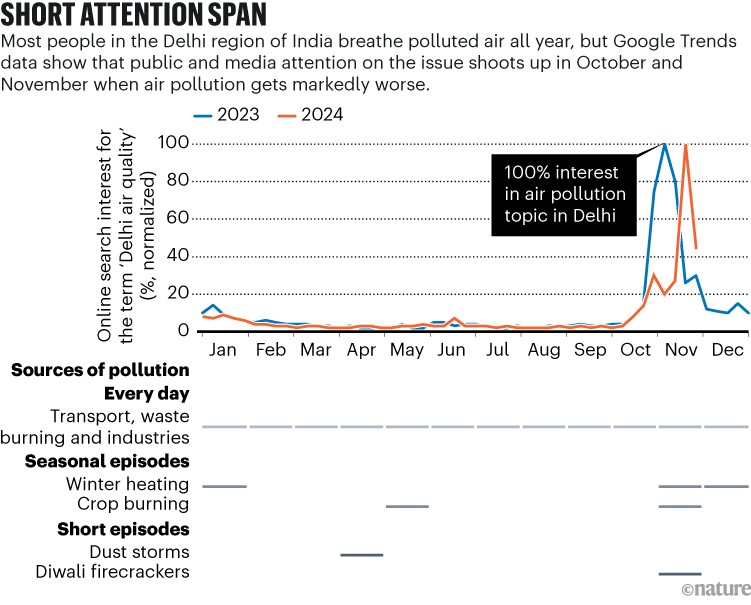

Despite pollution being a persistent, year-round problem, the media and policymakers often prioritize temporary fixes targeting the October–November spikes (see ‘Short attention span’). This needs to change.

Source: Google Trends

A comprehensive, year-round mitigation plan is required. Delhi’s case is illustrative of the challenges confronting the entire region. In 2019–22, the city’s annual average concentration of PM2.5 — harmful microscopic particles that can penetrate deep into the lungs and bloodstream — was about 20 times higher than the WHO’s clean air standard1. Most people in South Asia breathe polluted air throughout the year, resulting in a reduction in average life expectancy of about five years.

Over the past 25 years, studies have consistently shown that vehicle and freight transport in Delhi contributes significantly to air pollution, accounting for 10–30% of all human-induced emissions there. Other key sources include the burning of biomass and coal for residential cooking and heating (which peaks in the winter months), industrial emissions (10–30%, varying across regions), open waste burning (up to 15%) and dust (up to 15%)1,2.

A unified action plan is required to tackle these sources of pollution simultaneously. Here are five key steps that will make a difference.

Boost public transport

The opening of the Delhi Metro in 2002 was a key milestone for the growing city, which desperately needed an alternative mass-transportation system. But it hasn’t reduced people’s reliance on motorized transport. A 2011 survey by researchers at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi showed that around 54% of the Metro’s riders previously used buses or non-motorized transport; less than 15% used to travel by motorcycle and 25% previously used a car (respondents could choose more than one transport mode)3. In effect, the number of vehicle kilometres undertaken by private motorized transport did not fall significantly.

Local government actions can curb air pollution in India and Pakistan

Borrowing from pollution mitigation strategies adopted by cities such as London, Paris and Singapore, Delhi could start to discourage motorized transport by levying high taxes on the purchase of personal vehicles and introducing road-usage charges, while expanding bus- and rail-based public transport. Currently, Delhi has more than 10 million registered personal vehicles, but fewer than 8,000 public-transport buses.

In the late 1990s, following the intervention of India’s Supreme Court, all diesel-powered buses and taxis in Delhi were mandated to convert to compressed natural gas, which emits markedly lower levels of PM2.5 per vehicle kilometre. So far, this remains the most notable success story in Delhi’s efforts to manage air quality. However, the initial gains have been erased by the constant expansion in private vehicles.