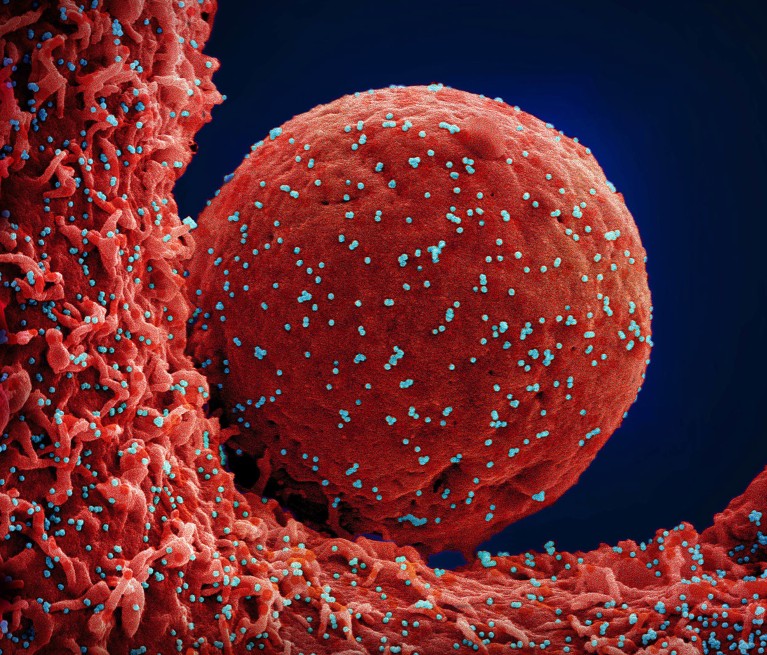

A cell (red) infected with SARS-CoV-2 virus particles (blue).Credit: NIAID/National Institutes of Health/Science Photo Library

A signalling molecule that helps to kick-start inflammation in the lungs could play a key part in aggravating some long COVID symptoms, finds a study that analysed lung samples from people with the condition.

The findings, published in Science Translational Medicine on 17 July1, could help scientists to develop more effective treatments for long COVID, which causes symptoms such as brain fog, fatigue, breathlessness and lung damage and can persist for months or years after infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind COVID-19.

By inhibiting the molecule — called interferon gamma (IFN-γ) — in mice with COVID-19, “we were able to dampen the chronic conditions after infection”, says study co-author Jie Sun, an immunology researcher at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. “In the future, we could target this pathway for potential treatment of long COVID”.

Inflammation protein

IFN-γ is one of many proteins that the body releases to fight infections. When released by white blood cells known as T cells, it sends signals to other immune cells and promotes inflammation. In the short term, this increases blood flow to the infected area to support the healing process — but chronic inflammation can cause damage to cells and tissues.

Previous research has shown that people with long COVID have elevated levels of IFN-γ2, and evidence also suggests that the protein can contribute to injuries in the alveoli3 — the delicate air sacs in the lungs that move gases into and out of the bloodstream. But these studies could not determine whether IFN-γ is a cause of lung damage associated with long COVID or just an indication of another mechanism.

Long COVID still has no cure — so these patients are turning to research

To investigate this, Sun and his colleagues took a two-step approach. First, they recruited people with long COVID and compared samples of cells from their lungs with those of people who had recovered from COVID-19 a few weeks before the study, as well as a controls who hadn’t been infected. They used a technique called single-cell RNA sequencing to analyse the make-up of the lung-cell samples. They discovered that samples from people with long COVID had higher levels of IFN-γ-producing T-cells than did samples from people without COVID-19, or those who had recovered from the infection.

Then, the researchers infected mice with SARS-CoV-2. Twenty-one days after infection, the mice had a cellular response in their lungs similar to that seen in people with long COVID, including elevated levels of IFN-γ-producing T cells.

The researchers treated some of the infected mice with a compound that inhibits IFN-γ. They noticed a great improvement in the animals’ health — an overall reduction in inflammation in the lungs, lower levels of immune cells that promote inflammation and fewer deposits of collagen, a substance that can damage and scar lung tissue.

Future treatments

The team hopes that targeting IFN-γ could have similar benefits for people with long COVID. “The next step would be to see if we can use a treatment which impacts this pathway to see if symptoms are improved in patients,” says Stéphanie Longet, an immunologist at the International Centre for Infectiology Research in Lyon, France, who has long COVID herself. She adds that there are already IFN-γ-inhibiting drugs on the market, such as baricitinib, which is currently used to treat severe COVID-19 and to reduce inflammation caused by rheumatoid arthritis.

The researchers also stress the importance of investigating other potential drivers of long COVID, which is thought to affect millions of people worldwide. “What we found here is probably one factor in one long COVID condition,” says Sun. “We want to look at more kinds of mechanisms to help identify more targets in the future.”