Last year, Kutubuddin Molla disappointed a postdoctoral colleague who had sought his advice about a conference in Italy. “I quickly recognized it as predatory. They invited him as a keynote speaker, despite him not having any publications in that field yet,” Molla says.

Like his colleague and many other scientists, Molla, a plant geneticist at India’s National Rice Research Institute in Cuttack, often receives invitations to present papers at conferences that are completely unrelated to his field, focused on topics such as architecture or waste management.

Ten years earlier, during his PhD programme at the University of Calcutta in Kolkata, India, Molla was invited to attend a conference on genetic engineering. It was put on by OMICS, a publisher and conference organizer based in Visakhapatnam, India, that has been fined for engaging in deceptive business practices. OMICS wanted him to give either a poster or an oral presentation. “I had no idea that conferences could be predatory,” he says.

What is it like to attend a predatory conference?

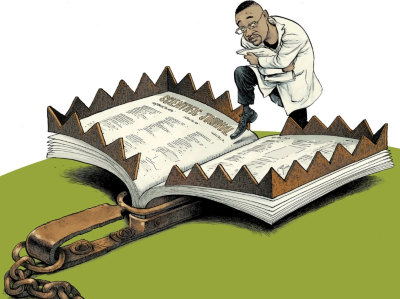

Predatory conferences typically include weak or no peer review for presentations, poor organization and a focus on profitability. In Molla’s case, the day after submitting an abstract, he was accepted to give a poster presentation. The next day, he says, a conference representative told him that he had been selected to deliver an oral presentation, urging him to register immediately at a cost of US$1,200. He was unable to find the funds to register and travel. Eventually, after seeing what he felt was the poor quality of a journal published by OMICs, he realized that it had been a near miss. “I consider myself fortunate to have avoided attending the predatory conference and publishing with them,” Molla says.

Nature contacted OMICS for comment, but did not receive a reply.

In the first article in this two-part investigation into predatory conferences, researchers recounted their experiences of predatory conferences. Here, we explore what actions to take to avoid them (see ‘Top tips’).

Would a central list of problematic conferences help researchers to decide which ones to attend? Jeffrey Beall, a retired academic librarian and library scientist, based in Walsenburg, Colorado, who once compiled Beall’s List of predatory publishers, is sceptical. He never kept a list of predatory conferences, because he felt that tracking them would be impossible. “They would appear and disappear quickly. Many of them are ephemeral,” he explains.

Beall, who in 2017 took down his list of predatory journals and publishers under what he has called intense employer pressure, thinks that lists of high-quality conferences in each discipline could be helpful. A conference-evaluation checklist called ‘Think. Check. Attend.’, run by Knowledge E, a research consultancy based in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, assists researchers in assessing conference quality.

More steps

As Molla’s experiences demonstrate, checking with a senior colleague or mentor can be useful. Diane Negra, a film-studies and screen-culture researcher at University College Dublin, who co-chairs the InterAcademy Partnership — an international network of more than 140 science academies — says that junior researchers don’t know instinctively which conferences are legitimate. Mentors and supervisors should advise their early-career colleagues on which conferences are worth attending.

Predatory conferences are on the rise. Here are five ways to tackle them

Checking previous conference proceedings (if they exist) could also give early-career researchers a sense of the event’s academic quality. ResearchGate and other online discussion forums are another way to pool information about conferences.

In April 2021, Dikoma Shungu, a radiology researcher at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City, received an invitation to present a paper at the November 2021 European Society of Medicine (ESMED) Congress in Vienna, which he accepted. But later, after he clicked on a link to the website, it was flagged as suspicious by his university’s information-technology team. Subsequent Google searches revealed that the conference organizer was touting him as a “featured speaker” and had used a photo of him without permission on the event website. Shungu contacted the conference organizers, but received no response to his repeated queries. “It’s then that I decided that it was a fake conference,” he says. So he asked his credit-card company to refund the conference fee.

Nature’s reporter spoke to an attendee of another ESMED event, the 2021 ESMED General Assembly in Berlin, who remembered one researcher giving a presentation to an otherwise empty room.

This wasn’t the end of the story, however. Shungu says that ESMED continued to use his presentation abstract and photo and list him as a featured speaker for the following year’s General Assembly, without his consent.

Several researchers contacted as part of this investigation criticized ESMED for sending insistent e-mails inviting speakers to conference sessions that they were unqualified to speak at or that did not actually take place. The Vienna event even featured a keynote speaker who was deceased.

I’m worried I’ve been contacted by a predatory publisher — how do I find out?

An ESMED representative says that the company no longer runs events and “put an immense amount of effort into planning our November 2021 event, and received positive feedback from several participants. Three months prior to the event we contacted each speaker to confirm they are still planning to come, and deleted from our programme anyone who didn’t confirm. Unfortunately, the keynote section of the programme was overlooked during this process. Overall, the event went quite well considering that it was our society’s first event of that size, and took place during a pandemic.” The spokesperson says that the COVID-19 pandemic helped to explain low attendance numbers at the Berlin conference.

“If a conference is truthful and accurate in its communications and materials, then it may not be of exceptional quality, but it is not predatory,” the representative adds. “If any one of our past clients is dissatisfied with the service they received they may contact us using the contact form or e-mail on our website, and we promise to make it right.”

James McCrostie, a business-administration researcher at Daito Bunka University in Tokyo, says that simply googling the conference company’s name often reveals its track record (or lack of it).

“In many academic systems, career progression relies on evidence of international conference presentations, but because there is no robust quality check, predatory companies have stepped in to meet the demand,” McCrostie says.

Institutional action

In 2019, South Korea’s education ministry introduced a requirement for the country’s universities to vet academics’ overseas conference travel. The decision came after a report revealed that 574 professors at 90 universities had participated in conferences that it called “weak”.

One initiative that might help is the information platform Scholarly Ecosystem Against Fake Publishing Environment (SAFE), administered by the Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information (KISTI), headquartered in Daejeon. Yong-il Jeong, a science- and technology-policy researcher at KISTI, describes SAFE as “a public service that globally monitors suspected insolvent academic journals and predatory academic events worldwide”. The SAFE map tracks the numbers and locations of conferences organized from 2015 onward by OMICS and the World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology (WASET), another company that is often described as predatory.

How I overcame my stage fright in the lab

WASET rejects the suggestion that its events are weak or suspect. A spokesperson says that the organization has a thorough review process for papers and conference talks, and that it maintains an open-access database of its proceedings. OMICS was also contacted about its inclusion on SAFE’s watchlist, but had not replied by the time this article went to press.

Stop Predatory Practices, an initiative that is similar to SAFE, was developed by the Czech Academy of Sciences in Prague. It includes a teaching module on predatory practices, which roughly 300 people have completed so far, says Tereza Šímová, an open-science advocate at OpenAIRE, a non-profit organization based in Athens, and at the Institute of Philosophy at the Czech Academy of Sciences.

Predatory organizers sometimes host conferences at university facilities — lending an air of credibility to the events. Such conferences can also provide an important income stream for academic institutions at a time when many are cash-strapped.

Hynek Janoušek, a philosophy researcher at the Institute of Philosophy at the Czech Academy of Sciences, says that universities should apply quality-benchmarking measures to conferences attended by academic staff, comparable to those that they use to assess journals. “If I was a university, I certainly would check,” he says. “If you check what kind of journals people publish in, then you should also check what kind of conferences they attend.” Negra adds: “It is important for universities to have ethical facilities-rental policies in place to ensure that (however unwittingly) they do not facilitate predatory events.” This could be especially significant for prestigious universities in high-income countries, whose reputations are part of the allure for conference attendees.

Individual responsibility is only one part of the puzzle, given the increasing sophistication of predatory conferences and the complexity of the academic reward system. Although there’s no silver bullet, it’s helpful to start with the recognition, as McCrostie says, that predatory conferences leave in their wake disgruntled delegates who have parted with hard-won grant funds to attend an event with little benefit to their careers.