Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

A researcher examines the foot of a mammoth calf retrieved from Siberian permafrost.Credit: Love Dalén, Stockholm University

Scientists have discovered intact chromosomes preserved in the skin of a woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) that met its end some 50,000 years ago — a feat previously thought to be impossible. The team also revealed the spatial organization of the mammoth’s DNA molecules and the active genes in its skin, including one responsible for giving the animal its fuzzy appearance. The study is the first to report the 3D structure of an ancient genome, says molecular archaeologist Ludovic Orlando. “This work is simply unprecedented.”

Cases of H5N1 avian influenza continue to rise in cattle in the United States. Countries are preparing for the possibility that the virus could spark a pandemic in people by ramping up surveillance, as well as purchasing vaccines or developing new ones. The Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) is working to ensure that the response is equitable worldwide. Their approach “for the moment is one of ‘calm urgency’” — “like putting our shoes on in case we need to start running”, says Nicole Lurie, who heads preparedness and response at CEPI.

An employment court in New Zealand has ruled that the University of Auckland breached obligations to protect microbiologist Siouxsie Wiles from abuse and harassment she experienced while providing public information about the COVID-19 pandemic. But the court did not find that the university had suppressed Wiles’ academic freedom when it advised her to keep her public commentary to a minimum to reduce the harassment. Wiles told Nature that the most important section of the judgment for academics might be “that providing this expert commentary is part of our jobs and that, because it’s part of our jobs, our employers need to keep us safe”.

Reader poll

Last month, the 210,000 people in Estonia who contributed to the country’s biobank were given access to data such as their genetic risk for certain diseases. Informing so many people about their genomes is easier said than done: for example, counsellors had to speak to 5,000 individuals with a high genetic risk of certain conditions. And the programme went through two years of back-and-forth with an ethics review board.

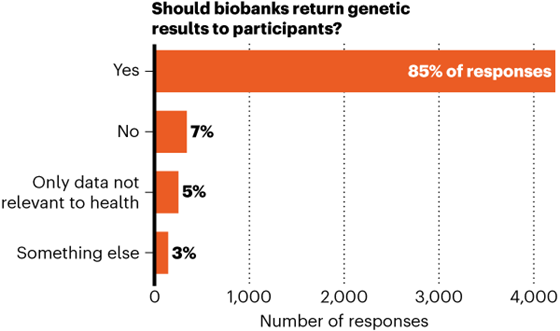

Readers who responded to our survey overwhelmingly agreed that biobanks should return genetic results to participants. “Instead of patronizing the participants I would let them decide themselves,” says neurogeneticist Wiebke Möbius. “After explaining the ethical implications they should choose how much information they want.”

Many pointed to the importance of counselling alongside receiving information about the risk for certain conditions — particularly those that lifestyle changes can’t address. “Information about untreatable future diseases will only increase anxiety and lead to stress which itself is a harbinger of diseases,” argues biotechnology researcher Praveen Balgir.

Psychologist Kairen Cullen adds that more research is needed into the psychological effects of biodata research. “This should also explore why and how individuals become involved with projects that mine their personal biodata.”

Features & opinion

In the late 18th century, papers that were read aloud at meetings of the Royal Society were minuted by secretaries as short summaries — known as ‘abstracts’. Historian Aileen Fyfe explains how these skillfully shortened versions, and other efforts to condense and disseminate the scientific literature, metastasized into the obligatory 200-word brain-teaser that tops most scientific papers today.

Nature Reviews Physics | 8 min read

Any parent who’s spent an evening swiping through old photos of their kids suggested by an algorithm (yep, that’s me!) must read the latest short story for Nature’s Futures series.

Andrew Robinson’s pick of the top five science books to read this week includes a history of accidental scientific discoveries, a compelling analysis of psychiatry’s role in medicine and an alternative view of intelligence as ‘educability’.

During breastfeeding, bones are stripped of calcium, and levels of oestrogen (which normally helps to keep bones healthy) plummet. But bones don’t break down — and a hormone produced in the brains of lactating mice suggests why. ‘Cellular communication network factor 3’ promotes the build-up of bones, keeping them strong during milk production. “You’re really rejuvenating this whole system,” says physiologist and study co-author Holly Ingraham.

Nature Podcast | 27 min listen

Subscribe to the Nature Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or YouTube Music, or use the RSS feed.