Alamy

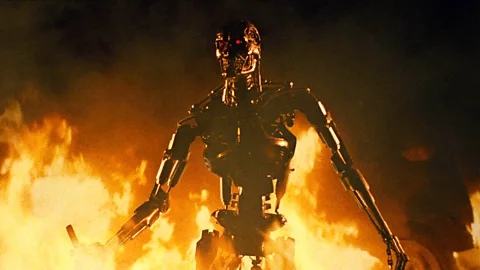

AlamyStarring Arnold Schwarzenegger, the 1984 blockbuster The Terminator has become synonymous with the dangers of superintelligent machines. But it “helps and hinders” our understanding of AI.

In one episode of the HBO sitcom Silicon Valley, Thomas Middleditch (Richard Hendricks) is explaining his machine-learning platform Pied Piper to a focus group when one participant inevitably compares it to James Cameron’s 1984 film The Terminator. “No, no, no,” insists the exasperated Middleditch. “I can assure you that there is no Skynet type of situation here. No, Pied Piper will in no way become sentient and try to take over the world.” Too late. He’s lost the room.

With its killer robots and its rogue AI system, Skynet, The Terminator has become synonymous with the spectre of a machine intelligence that turns against its human creators. Picture editors routinely illustrate articles about AI with the chrome death’s head of the film’s T-800 “hunter-killer” robot. The roboticist Ronald Arkin used clips from the film in a cautionary 2013 talk called How NOT to build a Terminator.

Alamy

AlamyBut the film is a mixed blessing. The philosopher Nick Bostrom, whose 2014 book Superintelligence popularised the existential risk of “unaligned AI” (AI that is not aligned with human values and wellbeing) admitted that his wife “teases me about the Terminator and the robot army”. In his book The Road to Conscious Machines, AI researcher Michael Woolridge frames an entire chapter with a complaint about “the Terminator narrative of AI”.

There are more recent, and more plausible, influential films about AI, including Ex Machina and Her, but when it comes to the dangers of the technology, The Terminator reigns supreme 40 years after its release. “It’s almost, in a funny way, more germane now than it was when it came out,” Cameron told The Ringer about the film and its 1991 sequel, “because AI is now a real thing that we have to deal with, and then it was a fantasy.”

‘Anti-gun and anti-machine’

This is quite an achievement for a film that is not, in fact, particularly interested in AI. First and foremost, it is a lean and lurid thriller about an unstoppable “man” chasing a scared but resourceful woman. The T-800 is an implacable killer in the vein of Michael Myers from Halloween. Cameron called it “a science-fiction slasher film”. Secondarily, it is a time-travel film on the theme of “fate vs will”, as Cameron put it.

The briskly sketched premise is that at some point between 1984 and 2029, the US entrusted its entire defence system to Skynet. One day, Skynet achieved superintelligence – a mind of its own – and initiated a global nuclear war. Humanity’s survivors then waged a decades-long rebellion against Skynet’s robot army. By 2029, the human resistance is on the verge of victory thanks to the leadership of one John Connor, so Skynet dispatches a T-800 (Arnold Schwarzenegger) to 1984 to kill John’s mother-to-be Sarah (Linda Hamilton) before she becomes pregnant. The resistance responds by sending back Kyle Reese (Michael Biehn) to stop the T-800 and save Sarah. In one of those time-loop paradoxes that viewers should not examine too closely, Kyle hooks up with Sarah and turns out to be John’s father. The future is saved.

Alamy

AlamyThe Terminator, then, is a thriller, a love story, a time-hopping rumination on free will and a satire about our dependence on technology. It is anti-corporate, anti-war, anti-gun and largely anti-machine. Technology, from answering machines to Walkmans, is involved when people get killed in this film. But it has very little to say about AI itself.

The Terminator would become one of the most profitable films of all time, grossing $78.4m, but Cameron had no expectation of creating a cultural touchstone. He wrote the screenplay in a tatty hotel in Rome in 1982 after being fired from his first directing gig, Piranha II: The Spawning, and his producer Gale Ann Hurd could only rustle up a $6.4m budget. His lead actor, a former bodybuilder of unproven talent, did not have high hopes. Schwarzenegger told a friend about “some shit movie I’m doing, take a couple of weeks”.

Cameron himself expected The Terminator to get “stomped” at the box office by the autumn’s two sci-fi epics: David Lynch’s Dune and Peter Hyams’s 2010: The Year We Make Contact, a soon-forgotten sequel to 2001: A Space Odyssey. There’s an attractive synchronicity here: not only did The Terminator outperform 2010 but Skynet came to supplant 2001’s murderous computer HAL 9000 as the dominant image of AI gone bad.

Long before the field of AI existed, its potential dangers manifested in the form of the robot, created by Karel Čapek in his 1921 play RUR and popularised by Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis. In his excellent BFI book on The Terminator, Sean French suggests that the movie’s most memorable image – the T-800 striding out of the flames, its suit of flesh melted away to expose its metallic endoskeleton – was a nod to the burning robot in Metropolis. In the 1920s, it stood to reason that machine intelligence would walk and talk, like Frankenstein’s monster. The popularity of lethal robots led the science-fiction writer Isaac Asimov, in 1942, to draw up the “three laws of robotics”: the first ever attempt to define ethical AI.

In the real world, the field of artificial intelligence officially began in 1956 at a summer school at Dartmouth University, organised by computer scientists John McCarthy (who coined the term) and Marvin Minsky. Their ambition was to design machines that could think like humans, but this proved much harder than they had imagined. The history of AI is one of boom and bust: a cycle of so-called “AI springs” and “AI winters”. Mindboggling promises attract attention, funding and talent; their failure to materialise causes all three to slump.

Alamy

AlamyThe boom of the 1960s, before the scale of the technical obstacles became apparent, is known as the Golden Age of AI. Extravagant hype about “electronic brains” excited director Stanley Kubrick and writer Arthur C Clarke, who integrated AI into 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey in the form of HAL 9000. The name (meaning Heuristically Programmed Algorithmic Computer) came from Minsky himself, hired as a consultant by Kubrick. The T-800’s red eyes are surely a homage to HAL – seeing 2001 as a child set Cameron on the path to becoming a film-maker.

Daniel Crevier, a historian of AI, contrasted the HAL scenario (poorly programmed computer goes awry) with the scenario in DF Jones’s 1966 thriller Colossus (computer becomes a god-like new lifeform). In Jones’s novel, the US government unwisely entrusts its entire defence machinery to the titular supercomputer. Colossus achieves sentience, joins forces with its Soviet counterpart and blackmails humanity into submitting to a techno-dictatorship: surrender or face nuclear annihilation. Colossus is a proto-Skynet.

The end of history

Neither HAL nor Colossus had – or needed – bodies. Cameron’s brilliant innovation was to combine the out-of-control computer (Skynet) with the killer robot (the T-800). The T-800 is a single-purpose form of AI that can learn from its environment, solve problems, perform sophisticated physical tasks and deepfake voices, yet struggles to hold a conversation. Skynet, it seems, can do everything but move.

Skynet was a product of the second AI spring. While Cameron was writing the screenplay, the British-Canadian computer scientist Geoffrey Hinton was rethinking and reviving research into the neural-net approach to AI: modelling machine intelligence on the neurons in the human brain. Skynet is neural-net AI. Hinton, who has just won the Nobel Prize for physics, has recently become an AI doomer (“My intuition is: we’re toast. This is the actual end of history”), but according to a New Yorker profile, he enjoyed The Terminator in 1984: “It didn’t bother him that Skynet… was a neural net; he was pleased to see the technology portrayed as promising.”

The name Skynet may also have been a nod to Star Wars, President Reagan’s doomed dream of creating an anti-nuclear shield around the US with space-based lasers. (Fortunately for the franchise’s future, it also inadvertently echoed the internet – a word that existed in 1984 but was not widely used until the 1990s.) The portmanteau names of ambitious new start-ups like IntelliCorp, Syntelligence and TeKnowledge possibly inspired Cameron to crunch down the original name of Skynet’s creator, Cyber Dynamics Corporation, into Cyberdyne Systems.

Rewatching The Terminator now, it is surprising to find that the word Skynet is only uttered twice. According to Kyle Reese it was: “New. Powerful. Hooked into everything. Trusted to run it all. They say it got smart… a new order of intelligence. Then it saw all people as a threat, not just the ones on the other side. Decided our fate in a microsecond… extermination.” That’s the extent of the film’s interest in AI. As Cameron has often said, the Terminator films are really about people rather than machines.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe blockbuster 1991 sequel Terminator 2: Judgment Day filled out the story a little. It springs from another time paradox: the central processing unit and right arm of the original Terminator survived its destruction and enabled Cyberdyne scientist Miles Bennett Dyson (Joe Morton) to design Skynet. The heroes’ task now is not just to save 10-year-old John Connor from the time-travelling T-1000 but to destroy Skynet in the digital cradle. (This was Cameron’s last word on the subject until he produced and co-wrote 2019’s Terminator: Dark Fate. He recently told Empire magazine that all the intervening sequels were “discountable”.)

In Terminator 2, a Schwarzenegger-shaped T-800 is protector rather than hunter, and therefore the bearer of exposition: “The system goes on-line August 4th, 1997. Human decisions are removed from strategic defence. Skynet begins to learn at a geometric rate. It becomes self-aware at 2:14 a.m. Eastern time, August 29th. In a panic, they try to pull the plug.” Skynet fights back by launching nuclear missiles at Russia, in the knowledge that the counter-attack will devastate the US. Three billion people die in 24 hours: Judgement Day.

This is a fundamentally different account to Reese’s. In the first film, Skynet overinterprets its programming by deeming all of humanity a threat. In the second, it is acting out of self-interest. The contradiction does not trouble most viewers, but it does illustrate a crucial disagreement about the existential risk of AI.

The layperson is likely to imagine unaligned AI as rebellious and malevolent. But the likes of Nick Bostrom insist that the real danger is from careless programming. Think of the sorcerer’s broom in Disney’s Fantasia: a device that obediently follows its instructions to ruinous extremes. The second type of AI is not human enough it lacks common sense and moral judgement. The first is too human – selfish, resentful, power-hungry. Both could in theory be genocidal.

The Terminator therefore both helps and hinders our understanding of AI: what it means for a machine to “think”, and how it could go horrifically wrong. Many AI researchers resent the Terminator obsession altogether for exaggerating the existential risk of AI at the expense of more immediate dangers such as mass unemployment, disinformation and autonomous weapons. “First, it makes us worry about things that we probably don’t need to fret about,” writes Michael Woolridge. “But secondly, it draws attention away from those issues raised by AI that we should be concerned about.”

Cameron revealed to Empire that he is plotting a new Terminator film which will discard all the franchise’s narrative baggage but retain the core idea of “powerless” humans versus AI. If it comes off, it will be fascinating to see what the director has to say about AI now that it is something we talk – and worry – about every day. Perhaps The Terminator’s most useful message to AI researchers is that of “will vs fate”: human decisions determine outcomes. Nothing is inevitable.

Dorian Lynskey is the author of Everything Must Go: The Stories We Tell About the End of the World (April 2024).