Illustration: David Parkins

The advice

Nature spoke to three senior scientists for advice, and they acknowledged that this is a very delicate situation that requires both honesty and care. Maria Augusta Arruda, a pharmacologist and director of the Brazilian Biosciences National Laboratory in São Paulo, Brazil, says that she tries to be as empathetic and honest as possible when declining to write a recommendation letter.

“There is always that tendency of trying to be almost passive aggressive, so you write the letter but you try to show that you’re not that enthusiastic about the person,” Arruda says.

“I really don’t think that’s the best thing to do.”

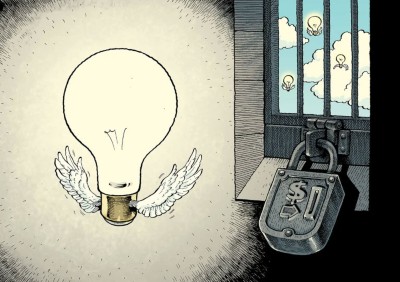

How can I publish open access when I can’t afford the fees?

Her approach is to tell the individual that she doesn’t feel that she’s the best person to write the letter, because “in my experience you did not have the chance to show all your attributes” while her employee. When she did say this to someone who had approached her for a recommendation letter, she was surprised at the response: the person thanked her for being open, and said that they regretted that their mutual experience had been like that.

James Murphy, a biochemist at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute in Melbourne, Australia, also says that his first response would be to suggest that he is not the best person to write the recommendation, and that there must be other people who are better equipped to write a letter of support. That’s particularly the case if he’s been approached by someone whom he has had a distant professional interaction with. “For a start, you don’t always have the best read on a person,” he says. “Secondly, there’s probably a reason why they’ve come to you rather than someone that they have worked more closely with.”

But sometimes writing a letter of recommendation is unavoidable, which poses a major conundrum for research leaders. “You’re staking your reputation on how they’re going to perform, so you want your word to be worth something”, Murphy says.

In this situation, letter writing is a balancing act. Murphy says that he doesn’t want to write negative letters, so his approach is to consider the individual in the most positive light possible while also noting their limitations in a constructive way.

My PI yelled at me and I’m devastated. What do I do?

An example might be to note in the letter that you haven’t had the opportunity to properly evaluate the applicant’s qualities in a particular area; for example, their organizational skills or their ability to work independently, “which is a pretty broad clue about a deficiency perhaps, but not damning”, Murphy says.

Another way to phrase it might be to describe those issues as ‘areas for development’, Arruda says, recognizing that it’s common for people to be skilled in some areas but not as much in others. For example, writing that “it will be good that in the next post that this person can exercise their leadership skills, or be supported to reach greater emotional balance”, is still giving that person a chance while also being open about the caveats, Arruda says.

Khatijah Yusoff, a microbiologist at the Institute of Bioscience at the University of Putra Malaysia in Serdang, says that she would give a frank opinion of the candidate’s abilities. “Sometimes, I would say that the candidate would need further training to improve in certain areas of work,” she says.

I was denied tenure — how do I cope?

It’s also important to recognize that an individual who has not performed so well in one setting might thrive in a different environment. “They may not have been a perfect fit for you and you may not have the best experience working with them, but in a different environment, they might end up being a superstar,” Murphy says.

Some scientists might be reluctant to be too critical in writing, in case there’s a chance the applicant will see it. Murphy’s advice is, if you want to clearly communicate your reservations or concerns about an applicant to a potential employer, it’s sometimes best to suggest in the letter that you are happy if they want to call to discuss it.

“If there’s someone that I’m not quite sure about, I would rather ring up someone and speak frankly rather than have it on a page,” he says. “Because there are things that you can’t say in a reference but you can say verbally.”

This is part of a series in Nature in which we share advice on career issues faced by readers. Have a problem? E-mail us at naturecareerseditor@nature.com