Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

Cryptocurrency will be used to reward peer reviewers for an experimental title called ResearchHub Journal.Credit: bizoo_n/Getty

The experimental publication ResearchHub Journal is paying peer reviewers the equivalent of US$150 per review in a specially developed cryptocurrency. The journal is hosted on ResearchHub, a platform backed by crypto entrepreneur Brian Armstrong, which aims to make science more open and efficient. “Getting paid to review is justice,” says molecular-biology consultant Pedro Paulo Gattai Gomes. But some other experts are cautious that the journal might struggle to gain a foothold in research publishing because of its unusual approach, and that the use of cryptocurrency could dissuade cautious academics.

Using tail-recognition software, researchers have tracked a humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) over 13,000 kilometres — the longest migration ever seen for the species. The whale’s odyssey, from the Atlantic off Colombia to the coast of Tanzania in the Indian Ocean over the course of almost a decade, is unusual for humpbacks, who normally stick to one section of the ocean. “This could be a simple story of a deeply confused whale,” says marine biologist Alexander Werth. “But it’s more likely that this intrepid explorer is a lonely male desperately seeking mates.”

Reference: Royal Society Open Science paper

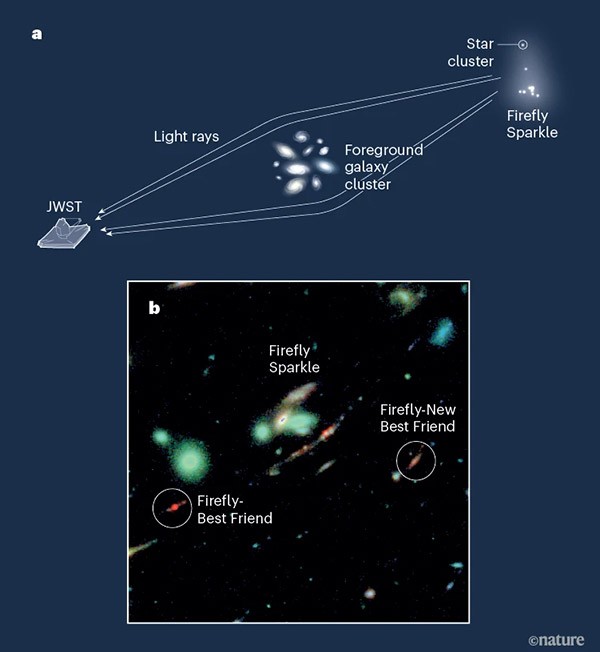

Images of a young galaxy captured by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope have given astronomers a glimpse of what the Milky Way might have looked like when it first formed. The images capture the galaxy, dubbed Firefly Sparkle after its resemblance to the bioluminescent insects, in the process of being assembled from groups of stars around 600 million years after the beginning of the universe.

a) Light from Firefly Sparkle and its surrounding stars was bent by the gravitational force of a cluster of other galaxies between it and the telescope, an effect called gravitational lensing. The effect of this distorted path is that the background object seems enlarged, as if it were being viewed through a cosmic magnifying glass. b) Images from the telescope captured Firefly Sparkle and two other young galaxies nearby, appropriately dubbed Firefly-Best Friend and Firefly-New Best Friend. (Nature News & Views | 7 min read, Nature paywall)

Features & opinion

Artificial intelligence (AI) is helping scientists to reveal what animals are saying to each other. Researchers have already leveraged the tool to discover that both African savannah elephants (Loxodonta africana) and common marmoset monkeys (Callithrix jacchus) have names. But it’s not as simple as building Google Translate for primate chatter. Such systems need huge amounts of well-defined training data, and it’s still an open question whether animals even have ‘language’ (and what ‘language’ is). Instead, AI can do things such as help researchers comb through recordings, separate sounds and assign them to individual animals. The ultimate goal, for many, is to help protect the creatures they’re studying. “If it were possible for humans to hear from other animals in their own words, ‘Hey, stop fucking killing us’, maybe people would actually do that,” says behavioural ecologist Mickey Pardo.

This article is part of Nature Outlook: Robotics and artificial intelligence, an editorially independent supplement produced with financial support from FII Institute.

To discover more on this topic, sign up for the free newsletter Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics.

Satellites can be effective environmental monitoring tools, but they’re no silver bullet, warns satellite expert Lorna Finman. To accurately measure releases of the potent greenhouse gas methane, satellites should be paired with boots on the ground to verify findings and overcome issues such as weather patterns that can distort readings. “Methane monitoring is too important to leave to one tool alone,” says Finman. “Let’s make sure we get this right.”

“We cannot expect those who do not understand how we live to build tools for us,” writes artificial-intelligence researcher Nyalleng Moorosi. She argues that making AI systems that are useful for research in Africa is not simply a case of adding more data to Western-built models, which are rarely trained on African languages or culture-specific data. Instead, the research community in Africa deserves opportunities to develop its own AI systems and regulations.

Today, I’m invested in an epic feline love story. Two unrelated Amur tiger (Panthera tigris altaica) cubs, Boris and Svetlaya, were raised together in captivity after being found orphaned. They were released separately into the wild at 18-months old. A year later, Boris had travelled almost 200 kilometres to where Svetlaya had settled, and they later became proud parents to their own litter.

More than a cute story, Boris and Svetlaya’s successful reintroduction into the wild has given scientists hope that the release of rescued cubs is a viable option for restoring the Amur tiger population.

Let us know how we can get you more invested in this newsletter at briefing@nature.com.

Thanks for reading,

Jacob Smith, associate editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Flora Graham

Want more? Sign up to our other free Nature Briefing newsletters:

• Nature Briefing: Careers — insights, advice and award-winning journalism to help you optimize your working life

• Nature Briefing: Microbiology — the most abundant living entities on our planet — microorganisms — and the role they play in health, the environment and food systems

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research — covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma