Eleanor Maguire wasn’t too thrilled when she was first offered an Ig Nobel Prize. The neuroscientist at University College London was being honoured for her study showing that London taxi drivers have larger hippocampi in their brains than do people in other professions1. But she worried that accepting the prize would be a disaster for her career. So, she quietly turned it down.

Three years later, the prize’s founder, Marc Abrahams, contacted Maguire again with the same offer. This time, she knew more about the satirical award that bills itself as honouring achievements that “make people laugh, then think”. She decided to accept. On the way to the ceremony, her taxi driver was so delighted to learn about his enlarged hippocampus that he refused to accept a fee from her.

Maguire credits the prize with bringing more attention to her work. “It was useful for my career because people wanted to talk about it,” she says, adding that “it was on the front pages of newspapers when it came out and struck a chord with people.”

How to win a Nobel prize: what kind of scientist scoops medals?

As one measure of the Ig Nobel’s impact, Maguire says that she was once introduced as “the most famous member” of a panel that happened to also include three Nobel laureates. “There were only questions about taxi drivers, and not anything to the Nobel laureates there.”

Other researchers have similar stories about winning the famous — some would say ‘infamous’ — awards. Abrahams created them in 1991, after years of collecting examples of weird research that he included in the Journal of Irreproducible Results, which he was editor of at the time. “I kept meeting people who’d unknowingly done very funny things that almost no one knew about.”

The response from the scientific community was mixed at the start, but Abrahams says that the Ig Nobels are not out to harm anyone’s career. And last year, the prize received more than 9,000 nominations, a sign of how much it has grown, he says.

Beyond the fun, several researchers who have won an ‘Ig’ say that it has improved their careers by helping them to reach wider audiences, and it has prompted some scientists to spend more time engaging with the public about their work. Here are their stories.

The duck guy

For Kees Moeliker, an Ig Nobel had a profound influence on his work — and his life. In 1995, the ornithologist was looking out of the glass wall of his office at the Natural History Museum Rotterdam in the Netherlands, when he heard the sound of a duck flying into it. He went outside and saw a live duck mounting the dead one that had just hit the window. It was the first documented case of homosexual necrophilia in ducks, says Moeliker, who reported his findings six years later2. He expected that only a handful of people would read the paper, but then he received a phone call in 2003 offering him an Ig Nobel Prize.

“After I won the prize, my paper got a huge readership, and people keep sending me stuff that you don’t read about in the mainstream journals,” he says. “I have a huge compilation of cases of remarkable animal behaviour.”

Kees Moeliker won an Ig Nobel prize for his work on homosexual necrophilia in ducks.Credit: Anne Claire de Breij

The duck paper and the Ig Nobel marked a turning point for Moeliker. He became known as ‘the duck guy’ and published a book of the same name: De eendenman (2009; in Dutch). In 2013, he gave a TED Talk titled ‘How a dead duck changed my life’.

Since the Ig Nobel, Moeliker has dedicated a large part of his life to science communication alongside his research. Now the director of the museum in Rotterdam, he has also kept up his connection with the Ig Nobels. He is part of the team that decides who wins, and he often informs scientists in Europe who have been selected.

One of his favourite winners was a pair of researchers who had dressed up as polar bears to study how reindeer in the Arctic would react. “When I called them, they just started screaming with happiness. This happens all the time.”

Friday-night experiments

The only person with both a Nobel and Ig Nobel Prize is Andre Geim, a physicist at the University of Manchester, UK. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2010 for the discovery of graphene, but the Ig Nobel came a decade earlier for a very different kind of work: using a magnet to levitate a frog. One Friday night at Radboud University in the Netherlands, Geim poured water into a powerful 16-tesla magnet and found that it levitated. The floating drop shocked his colleagues because it seemed to violate ideas about magnetism.

Success with water led to a series of other experiments with levitating objects — and eventually with a small frog that survived its wild ride unharmed.

You must be joking: funny paper titles might lead to more citations

When Geim was offered the award, he was an early-career researcher and wary of accepting it on his own. So he reached out to Michael Berry, a theoretical physicist at the University of Bristol, UK, and Geim’s co-author on a paper describing the levitating frog3. As a tenured academic, Berry provided the cover of being associated with a highly respected scientist.

Geim talks often about his frog experiment and the value of the curiosity-led science that led to his Ig Nobel Prize. It was on another Friday night, several years after the levitation experiments, that Geim and Konstantin Novoselov, who is now at the National University of Singapore, stuck a piece of tape to graphite, leading to their discovery of graphene4 — and their shared Nobel prize.

Geim and Maguire aren’t the only Ig Nobel winners who had qualms about accepting the prize. And Abrahams has built in allowances for that. He and his colleagues contact potential recipients confidentially months before the prize-giving ceremony and offer them the chance to accept or reject the award. Abrahams also arranges for them to be handed out by Nobel prize-winners at the annual ceremony. “To have these credible people be a part of it makes it much harder for anyone to jump to the conclusion that we are out to do damage,” he says.

Not everyone has been so pleased to receive the award. Eric Topol, a cardiologist at Scripps Research in La Jolla, California, was part of a group of nearly 1,000 people who won the 1993 Ig Nobel Literature prize for “publishing a medical research paper which has one hundred times as many authors as pages”. He says that the study should not have been made light of; at the time, it was the largest heart-attack study in history, with more than 40,000 participants5, he adds.

Topol says that he thinks the name Ig Nobel “is out of alignment with the more recent ones. They’re more for humour’s sake.”

Abrahams agrees, saying, “In retrospect, I kind of wish we’d chosen a different name.”

Running on water

In the past two decades, most of the awards have gone to lighter research — sometimes quite literally. So it was for a 2013 prize for Alberto Minetti at the University of Milan in Italy.

Minetti studies the biomechanics of locomotion and has long had an interest in the forces involved in running. When he learnt that spacecraft orbiting the Moon had detected evidence of water in 2008, he wondered whether a person could run on water on the Moon, which has a gravitational force only about 16% as strong as that of Earth.

Using mathematical models from the basilisk lizard (Basiliscus basiliscus) and the western grebe (Aechmophorus occidentalis), two vertebrates that can run on the surface of water, Minetti calculated that it was theoretically possible. Then, he and his colleagues tested their calculations by attaching a person to a harness to simulate weaker gravity. With the aid of small fins on his feet, a participant was able to stay afloat while running in place in a wading pool, the researchers reported6 in 2012.

The following year, Minetti received a phone call from Abrahams, who offered him an Ig Nobel. At the time, he wasn’t sure of the prize’s standing or what it would do to his reputation, so he conducted a survey among his colleagues. “Most of the people I spoke to were very positive about it,” says Minetti.

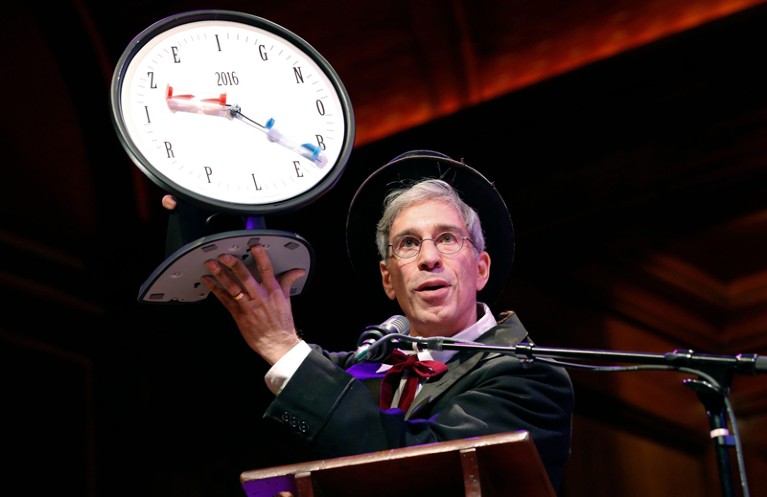

Marc Abrahams holds up the 2016 Ig Nobel award during ceremonies at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.Credit: Michael Dwyer/AP/Alamy

Fun and humour are still at the heart of the Ig Nobels. The 2024 physiology prize was won by a team for “discovering that many mammals are capable of breathing through their anus”. The lead author of the study7, Ryo Okabe at Tokyo Medical and Dental University, has been treating patients as a clinician for more than 15 years, while also carrying out research projects. The research behind the Ig Nobel was a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The researchers wanted to see whether they could develop an alternative breathing method in the event of respiratory failure.

He was honoured to win the prize and thinks that the award will be a driving force to conduct future research. “I learnt that [the other laureates] are all engaged in their respective research with humour and passion.”

Scientists reveal weirdest things they’ve done in the name of science

The Ig Nobel has come a long way since it was launched more than three decades ago. What started as a prize that scientists were wary of has been embraced by many.

Minna Lyons, who won the prize in 2014 along with her colleagues, still cherishes her Ig Nobel. “It has been one of the best surprises in my academic career, by far.” She won for “amassing evidence that people who habitually stay up late are, on average, more self-admiring, more manipulative, and more psychopathic than people who wake up early in the morning”.

Lyons, who is a psychologist at Liverpool John Moores University, UK, says that the prize is excellent for public engagement because it makes science popular, and for this reason, the Ig Nobel is one of the most respected academic awards in her field, she says.

“It actually inspires people and I’m hoping it will also inspire younger generations to go into science.”