Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

The Economics prize announced by Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences permanent secretary Hans Ellegren (centre), Jakob Svensson (left) and Jan Teorell of the Nobel Assembly.Credit: Christine Olsson/TT News/AFP via Getty

Why are some countries today richer than others? The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel — or the Economics Nobel, to its friends — has been awarded to economists Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson for their work investigating the influence of institutions on a country’s success. “They looked specifically at the history of European colonialism and the contrast in the fortunes of countries such as the United States or Australia vs countries in Sub-Saharan Africa or South Asia,” says economist Diane Coyle. “Countries that were already rich, or were places where European settlers did not survive well — because of illnesses or the climate — in these places, the colonial institutions were extractive,” Coyle says. “In contrast, in countries that were poorer to start with or had better climates, Europeans instead built more inclusive institutions similar to their own countries.” The result is that, paradoxically, “the parts of the colonized world that were relatively the most prosperous around 500 years ago are now those that are relatively poor,” notes the Nobel Prize organization.

Hair found wedged in the broken teeth of two infamous nineteenth-century lions (Panthera leo) offers a glimpse of their diet — which included people. The ‘Man-eaters of Tsavo’ terrorized workers constructing the Kenya-Uganda Railway. Analysing the DNA from these hairs revealed that the cats weren’t picky — they also chowed down on giraffes, oryx, waterbuck, wildebeest and zebra. Findings from the lions, which have been on display at Chicago’s Field Museum, demonstrate the value of reanalysing old specimens with new tools, say scientists.

Reference: Current Biology paper

As people living near the Gulf of Mexico recover from the onslaught of Hurricane Milton, scientists are explaining how the storm got so big, so fast. Part of the reason was a phenomenon called ‘eyewall replacement’, in which bands of rain coalesced to form an ever-larger boundary around the storm. “You can think of it as the shedding of its skin,” says atmospheric scientist Jonathan Lin. “Once it sheds its skin, it can re-intensify.” And record-high sea surface temperatures, which fuelled the intensity of Milton and of Hurricane Helene, were made 200 to 500 times more likely by climate change, says a report by the World Weather Attribution consortium of scientists.

NBC News | 7 min read & NBC News | 5 min read

Reference: World Weather Attribution report

Features & opinion

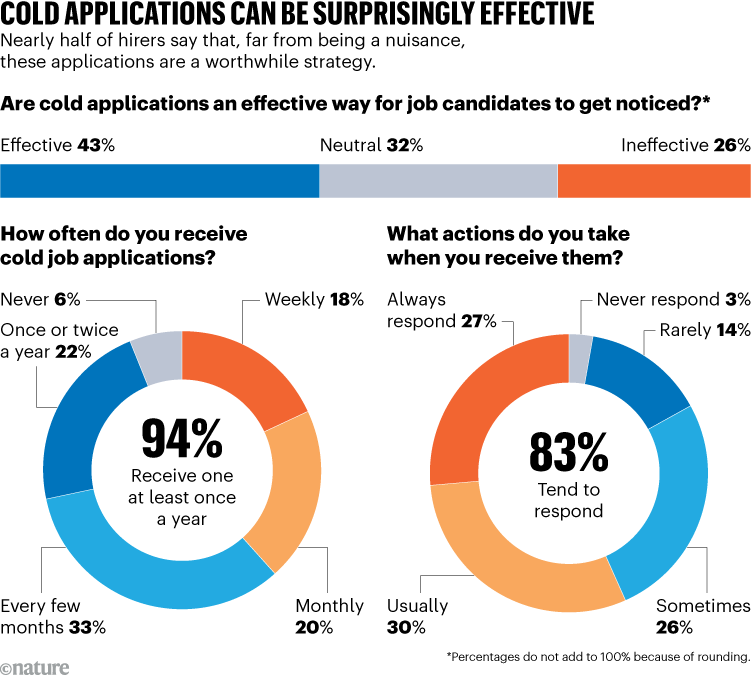

Nature has packaged the wisdom of hiring managers from across academia and industry into six charts to help you stand out as a candidate and avoid common missteps. It might not surprise you to learn it’s often not what you know but who you know. However, a cold application could be more successful than you think, and might even ‘shake loose’ an open position.

Science journalist Lisa Baril reveals the secrets of our ancestors entombed in ice patches in her new book, The Age of Melt. In interviews with environmental scientists and Indigenous communities whose traditional lands include artefact-bearing ice patches, Baril “takes the reader on a well-crafted and entertaining journey into Earth’s frozen realms”, writes climate scientist Joseph McConnell. The “extraordinary and unexpected” insights revealed by rapidly melting ice is an “upside” of climate change, says McConnell — but a fleeting one. “Once the ice melts, these links to the past will be lost to history.”

For large language models to move from mere prediction machines to tools that can mimic human common sense, computer sciences will need to wrestle with the fundamentals of cognition, argues a team of computer scientists. Humans do a great job of adapting our modes of reasoning and thinking on our feet. LLMs, not so much. To evaluate whether LLMs make progress, what’s required is theory-based benchmark tests that incorporate insights from cognitive science, philosophy and psychology, and to expand the focus beyond language to embodied systems that can sense messy real-world environments.

Image of the week

Part of SpaceX’s Starship rocket, the largest and most powerful rocket ever made, has been handily caught by a pair of metal arms nicknamed ‘chopsticks’. The first-stage booster, known as Super Heavy, gingerly placed itself within the arms of the ‘Mechazilla’ launch tower while the upper stage took a short test flight into space. The innovative manoeuvre is intended to eliminate the need for heavy landing gear and place the rocket in position for a quick-turnaround reuse. (CBS News | 6 min read) (SpaceX/Handout/Anadolu via Getty)

On Friday, Leif Penguinson was splashing around Lake Nakuru National Park in Kenya. Did you find the penguin? When you’re ready, here’s the answer.

If you wouldn’t mind, I’d be grateful if you’d answer this super-quick, one-question survey. Your response will only be used in aggregate to help us tailor this newsletter to best suit its readers, and certainly not to spam you with anything.

Thanks for reading,

Flora Graham, senior editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Jacob Smith and Josh Axelrod

Want more? Sign up to our other free Nature Briefing newsletters:

• Nature Briefing: Careers — insights, advice and award-winning journalism to help you optimize your working life

• Nature Briefing: Microbiology — the most abundant living entities on our planet — microorganisms — and the role they play in health, the environment and food systems.

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research — covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma