Absinthe, once the ‘Green Fairy’ – muse of painters and poets – came to haunt the last decades of 19th-century France. ‘Of all the alcoholic poisons that lead to crime, there is none more formidable than absinthe’, wrote a doctor – named only as ‘L’ – in the French temperance journal L’Alcool in January 1897. After the establishment and widespread acceptance of the diagnosis of ‘absinthism’ in the 1860s, analogous with but separate from alcoholism, people had begun to fear its consumption. The plant-based essential oils – from wormwood, aniseed, fennel, mint and more – that gave absinthe its distinct flavour, medico-psychiatric experts warned, could provoke murderous rage in its consumers. Not all absinthe drinkers descended into this green haze, but those who did were believed to randomly attack their loved ones, as well as complete strangers. It is commonly recognised today, however, that it was not the essential oils but simply absinthe’s high alcohol content that caused violence.

The French temperance advocate Paul-Maurice Legrain – very probably doctor ‘L’ – warned in his 1906 monograph Elements of Mental Medicine: ‘Never will a consumer, sitting down in full lucidity in front of his glass of absinthe, be able to affirm whether in a few moments he will not be committing a crime. The green hour [the time when absinthe was commonly consumed] is the red hour.’

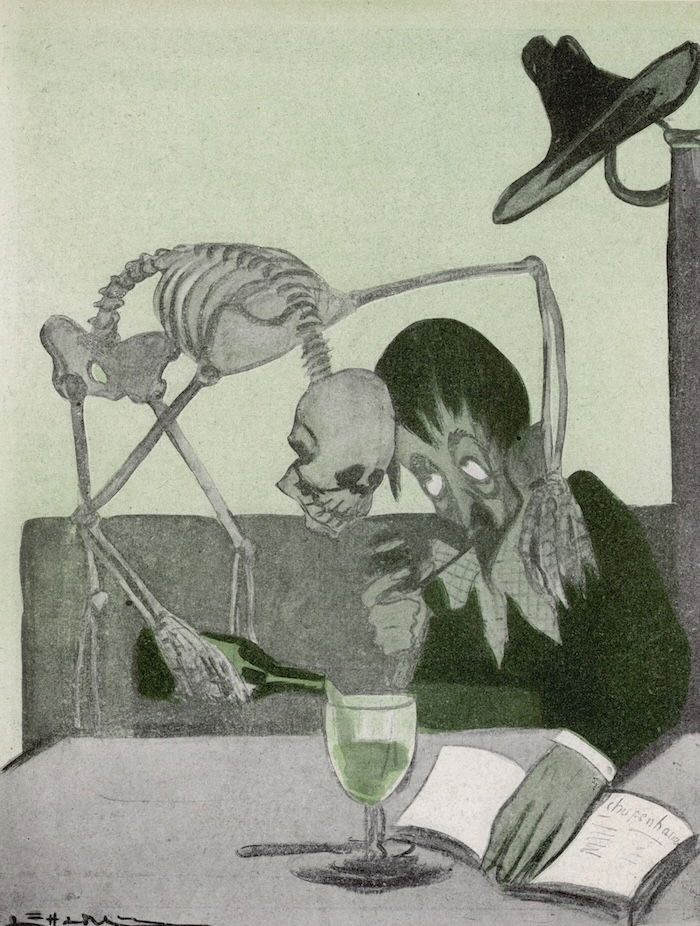

This perceived threat of absinthe-induced violence loomed over those innocently enjoying their early evenings on the terraces of fashionable cafés, as, especially in the 1880s and 1890s, sensational reports about so-called ‘absinthe murders’ appeared in French newspapers. La Presse Illustrée, for example, published an article on 21 October 1883 detailing four cases of murder and attempted murder under the influence of absinthe, allegedly occurring within a single week in France and Belgium, under the lurid title ‘The Crimes of Absinthe’. On the front page of this issue an illustration depicted a skeleton pouring a glass of absinthe next to a clearly drunk man. Around him are three smaller sketches: ‘madness’ shows two men fighting, restrained by policemen, with another man lying on the ground; ‘infanticide’ and ‘suicide’ have a row of graves above him.

Fears about the ‘Green Poison’, as it came to be called by its opponents, were reinforced by expert testimonials, such as the 1897 dissertation by the French doctor Robert H. Hazemann, ‘Homicides amongst Absinthics’. Hazemann presented 17 cases of murders ‘committed under the sole influence of absinthe’. These murderers’ deeds, he argued, were at odds with their usual sober comportment and they might, without the effects of absinthe, never have shown signs of extraordinary violence. Men – and, to a lesser degree, women – were believed to experience vivid hallucinations after consuming absinthe, followed by blind rage and a deep lack of empathy towards others, as well as loss of memory afterwards. These phases, medical experts like Hazemann argued, defined the experiences of both acute and chronic absinthism, i.e. of those who had drunk large amounts of it just before their deed, even if it had been their first encounter with the drink, and of those accustomed to it, even if they had not drunk absinthe on that specific day.

The most debated of these ‘absinthe murders’ took place on 28 August 1905 in the Swiss village of Commugny, where the French-born Jean Lanfray murdered his wife and two young daughters. While undoubtedly drunk at the time, it remains disputed whether he had consumed any absinthe that day. Yet his known habit of drinking absinthe was blamed. It was this local tragedy that solidified opposition towards the drink in Switzerland, followed by a countrywide petition for its ban, which was instituted in 1908. Both in Switzerland and in France, where absinthe was prohibited in 1915, fear of violence was an important factor in public discussions.

Such crimes influenced how the drink was perceived internationally, too. The Times, for example, reporting on the newly instituted French ban under the headline ‘French National Curse Suppressed’ in April 1915, spoke of absinthe causing convulsions, ‘nervous agitation, insomnia, and nightmares’, ‘hallucinations and profound mental troubles, which may lead to the Assize Court or to the asylum, or to both’. It continued: ‘Absinthe is a poison more powerful in murderous impulses than any other. Its victims sometimes run amok in provincial France.’ Such attacks were not presented as exceptional, but as examples of a widespread problem of absinthe-induced violence.

Underlying absinthe’s dramatic fall from grace was a change in consumers. Once the expensive drink of the French bourgeoisie and artists, absinthe became more affordable in the second half of the 19th century, whereupon workers, women and those in the French colonies, from North Africa to Indochina, began drinking it. Consequently, absinthe came to be blamed for working-class criminality in general and, more specifically, for the acts of the revolutionary Communards after the siege of Paris in 1871. The author Maxime du Camp, for example, described these Communards in his 1881 book Convulsions of Paris, as ‘knights of debauchery and apostles of absinthe’.

Panics about absinthe murders encapsulate how the drink came to be viewed in the years leading up to its ban. While many were undeterred by claims about its dangers, the causal link between absinthe and violence was uncontested in large parts of late 19th-century French society. The demonisation of absinthe also led to the trivialisation of alcohol and alcoholism in France: other spirits, wine, beer and cider were not believed to have comparable medical – or social – effects. Only the ‘Green Fairy’ could turn drinkers into uncontrollable, rage-filled criminals and therefore only absinthe had to be stopped. While absinthe was legalised in 2005 in Switzerland and in 2011 in France, its bad reputation endures.

Nina S. Studer is the author of The Hour of Absinthe: A Cultural History of France’s Most Notorious Drink (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2024).