People gather around a roadside pipeline to collect drinking water in Bangladesh.Credit: Mamunur Rashid/NurPhoto/Getty

Approximately 4.4 billion people drink unsafe water — double the previous estimate — according to a study published today in Science1. The finding, which suggests that more than half of the world’s population is without clean and accessible water, puts a spotlight on gaps in basic health data and raises questions about which estimate better reflects reality.

That this many people don’t have access is “unacceptable”, says Esther Greenwood, a water researcher at the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology in Dübendorf and an author on the Science paper. “There’s an urgent need for the situation to change.”

The United Nations has been tracking access to safely managed drinking water, recognized as a human right, since 2015. Before this, the UN reported only whether global drinking-water sources were ‘improved’, meaning they were probably protected from outside contamination with infrastructure such as backyard wells, connected pipes and rainwater-collection systems. According to this benchmark, it seemed that 90% of the global population had its drinking water in order. But there was little information on whether the water itself was clean, and, almost a decade later, statisticians are still relying on incomplete data.

“We really lack data on drinking-water quality,” Greenwood says. Today, water-quality data exist for only about half of the global population. That makes calculating the exact scale of the problem difficult, Greenwood adds.

Crunching numbers

In 2015, the UN created its Sustainable Development Goals to improve human welfare. One of them is to “achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all” by 2030. The organization updated its criteria for safely managed drinking-water sources: they must be improved, consistently available, accessible where a person lives and free from contamination.

The world faces a water crisis — 4 powerful charts show how

Using this framework, the Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (JMP), a research collaboration between the World Health Organization (WHO) and the UN children’s agency UNICEF, estimated in 2020 that there are 2.2 billion people without access to safe drinking water. To arrive at this figure, the programme aggregated data from national censuses, reports from regulatory agencies and service providers and household surveys.

But it assessed drinking-water availability differently from the method used by Greenwood and her colleagues. The JMP examined at least three of the four criteria in a given location, and then used the lowest value to represent that area’s overall drinking-water quality. For instance, if a city had no data on whether its water-source was consistently available, but 40% of the population had uncontaminated water, 50% had improved water sources and 20% had water access at home, then the JMP estimated that 20% of that city’s population had access to safely managed drinking water. The programme then scaled this figure across a nation’s population using a simple mathematical extrapolation.

By contrast, the Science paper used survey responses about the four criteria from 64,723 households across 27 low- and middle-income countries between 2016 and 2020. If a household failed to meet any of the four criteria, it was categorized as not having safe drinking water. From this, the team trained a machine-learning algorithm and included global geospatial data — including factors such as regional average temperature, hydrology, topography and population density — to estimate that 4.4 billion people lack access to safe drinking water, of which half are accessing sources tainted with the pathogenic bacteria Escherichia coli.

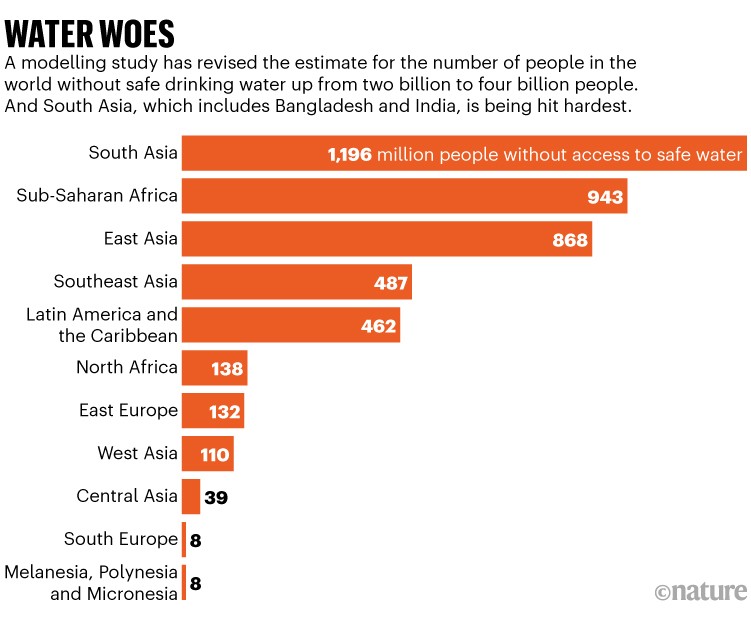

The model also suggested that almost half of the 4.4 billion live in south Asia and sub-Saharan Africa (see ‘Water woes’).

Source: Ref 1.

‘A long way to go’

It’s “difficult” to say which estimate — the JMP’s or the new figure — is more accurate, says Robert Bain, a statistician at UNICEF’s Middle East and North Africa Regional Office, based in Amman, Jordan, who contributed to the calculation of both numbers. The JMP brings together many data sources but has limitations in its aggregation approach, whereas the new estimation takes a small data set and scales it up with a sophisticated model, he says.

The study by Greenwood and colleagues really highlights “the need to pay closer attention to water quality”, says Chengcheng Zhai, a data scientist at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. Although the machine-learning technique used by the team is “very innovative and clever”, she says, water access is dynamic, so the estimation might still not be quite right. Wells can be clean of E. coli one day and become contaminated the next, and the household surveys don’t capture that, Zhai suggests.

“Whichever number you run with — two billion or four billion — the world has a long way to go” towards ensuring that people’s basic rights are fulfilled, Bain says.