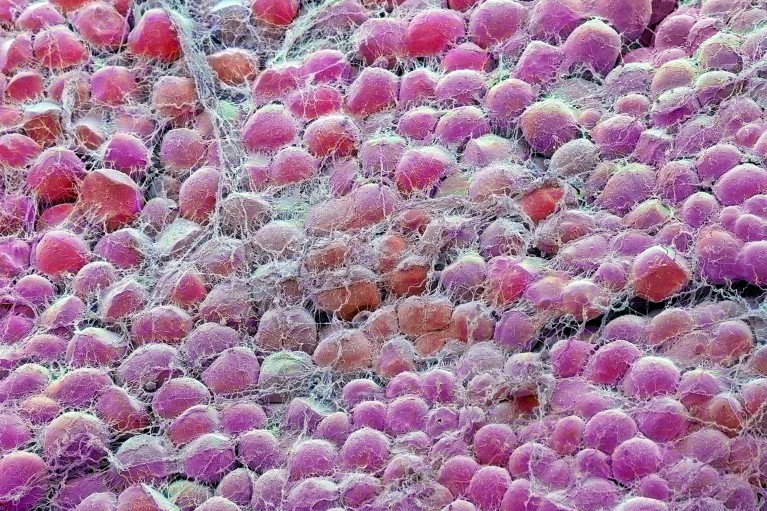

Fat cells (artificially coloured). Restrictive diets cause fat loss and lengthen life, but the two effects are not necessarily linked.Credit: Steve Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library

Cutting calorie intake can lead to a leaner body — and a longer life, an effect often chalked up to the weight loss and metabolic changes caused by consuming less food. Now, one of the biggest studies1 of dietary restrictions ever conducted in laboratory animals challenges the conventional wisdom about how dietary restriction boosts longevity.

The study, involving nearly 1,000 mice fed low-calorie diets or subjected to regular bouts of fasting, found that such regimens do indeed cause weight loss and related metabolic changes. But other factors — including immune health, genetics and physiological indicators of resiliency — seem to better explain the link between cutting calories and increased lifespan.

“The metabolic changes are important,” says Gary Churchill, a mouse geneticist at the Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, who co-led the study. “But they don’t lead to lifespan extension.”

To outside investigators, the results drive home the intricate and individualized nature of the body’s reaction to caloric restriction. “It’s revelatory about the complexity of this intervention,” says James Nelson, a biogerontologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio.

The study was published today in Nature by Churchill and his co-authors, including scientists at Calico Life Sciences in South San Francisco, California, the anti-ageing focused biotech company that funded the study.

Counting calories

Scientists have long known that caloric restriction, a regimen of long-term limits on food intake, lengthens lifespan in laboratory animals2. Some studies3,4 have shown that intermittent fasting, which involves short bouts of food deprivation, can also increase longevity.

To learn more about how such diets work, the researchers monitored the health and longevity of 960 mice, each a genetically distinct individual drawn from a diverse population that mirrors the genetic variability found in humans. Some mice were placed on calorie-limited diets, another group followed intermittent fasting regimens, and others were allowed to eat freely.

Life expectancy rise in rich countries slows down: why discovery took 30 years to prove

Cutting calories by 40% yielded the longest longevity bump, but intermittent fasting and less severe calorie restriction also increased average lifespan. The dieting mice also displayed favourable metabolic changes, such as reductions in body fat and blood sugar levels.

However, the effects of dietary restriction on metabolism and lifespan didn’t always change in lockstep. To the authors’ surprise, the mice that lost the most weight on a calorie-limited diet tended to die younger than did animals that lost relatively modest amounts.

This suggests that processes beyond simple metabolic regulation drive how the body responds to limited-calorie regimes. What mattered most for lengthening lifespan were traits related to immune health and red-blood-cell function. Also key was overall resilience, presumably encoded in the animals’ genes, to the stress of reduced food intake.

“The intervention is a stressor,” Churchill explains. The most-resilient animals lost the least weight, maintained immune function and lived longer.

Leanness for longevity

The findings could reshape how scientists think about studies of dietary restriction in humans. In one of the most comprehensive clinical trials of a low-calorie diet in healthy, non-obese individuals, researchers found5 that the intervention helped to dial down metabolic rates — a short-term effect thought to signal longer-term benefits for lifespan.

But the mouse data from Churchill’s team suggest that metabolic measurements might reflect ‘healthspan’ — the period of life spent free from chronic disease and disability — but that other metrics are needed to say whether such ‘anti-ageing’ strategies can truly extend life.

Daniel Belsky, an epidemiologist who studies ageing at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health in New York City, cautions against over-extrapolating from mice to humans. But he also acknowledges that the study “adds to the growing understanding we have that healthspan and lifespan are not the same thing”.